When it comes to women’s health, vaginal wellness is often missing from conversations about diet, but emerging research shows that what you eat can influence the delicate balance of bacteria in your vaginal microbiome.

Just like the gut, the vagina has its own unique community of microbes and nourishing this ecosystem with the right dietary choices may help:

Maintain an optimal pH

Support immune defences

Contribute to microbial balance1

The vaginal microbiome: why diet matters

The vaginal microbiome is usually dominated by beneficial Lactobacillus species. These bacteria produce lactic acid, which keeps vaginal pH in a low, acidic range (around 3.5–4.5), creating an environment that discourages the growth of potentially harmful microbes2.

While genetics, hormones, sexual activity, and hygiene practices all play important roles in microbiome balance, diet is now recognised as another potential influence1.

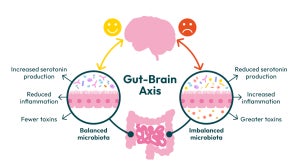

Researchers have identified a “gut–vagina axis”, where the gut microbiota may influence the vaginal microbiota via immune regulation, metabolic by-products, and hormonal pathways3. This means that a diet which promotes gut health may also support vaginal health though the exact mechanisms are still being explored.

Best foods for vaginal health

Certain foods provide nutrients and compounds that directly or indirectly support a balanced vaginal microbiome. These options can help maintain a healthy pH, encourage the growth of protective Lactobacillus species.

Fibre-rich plant foods

A diet high in fibre from vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds is linked to better gut health, and some studies suggest it may also support a healthier vaginal microbiome.

A study in 2016 found that women with higher fibre intake, particularly from fruits and vegetables, had significantly lower odds of having a low-Lactobacillus (molecular-BV) vaginal microbiota profile4.

Tip: Aim for at least 30g of fibre per day. Try lentil salads, overnight oats with berries, or vegetable and bean soups.

Micronutrient-rich vegetables and fruits

Eating a variety of colourful fruits and vegetables is a simple way to bring in vitamins and antioxidants that support overall wellbeing, including aspects of health linked to the vagina. Vitamin C, vitamin D and folate all contribute to the normal function of the immune system, while vitamin A helps to maintain normal mucous membranes. Vitamin E and β-carotene act as antioxidants, helping to protect cells from oxidative stress.

Different colours of fruits and vegetables often signal different nutrient profiles so mixing up your choices each week will cover a wider spectrum of beneficial nutrients.

Tip: Try adding berries to your morning oats or throwing a handful of leafy greens into a stir-fry.

Protein-rich foods

Some research has found that higher intakes of certain amino acids (building blocks of protein) are linked with a vaginal microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus. These include lysine, valine, leucine, and phenylalanine, which are found in foods like meat, fish, eggs, dairy, soy, beans, and lentils.

While we don’t yet fully understand the mechanisms, it’s thought these nutrients may help keep vaginal tissues healthy, support immune defences, and influence the balance of bacteria7.

Tip: Include a source of lean protein with each meal such as chicken, fish, eggs, tofu, beans, or lentils to naturally boost your amino acid intake.

Low-fat dairy and yoghurt

Consuming low-fat dairy products, including yoghurt, may support a healthier vaginal microbiome. In one study, higher intake of yoghurt was associated with a Lactobacillus-dominant vaginal microbiota.

This may be due to the presence of live bacterial cultures in yoghurt, such as Lactobacillus species, which can contribute to microbial balance, as well as nutrients like calcium and vitamin D that support immune function8.

Tip: Choose plain, live-culture yoghurt or kefir and pair it with fruit or nuts for a simple snack. If you’re dairy-free, look for fortified plant-based alternatives with added live cultures.

Starchy foods

Whole grains, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and legumes provide slow-release carbohydrates, which the body can store as glycogen. In the vaginal tract, glycogen in the epithelial cells is an important fuel for Lactobacillus beneficial bacteria that produce lactic acid and help keep vaginal pH in a healthy range.

While research directly linking dietary starch to vaginal microbiome balance is still limited, getting enough healthy starchy foods as part of a balanced diet may help support this process9.

Tip: Try adding a small serving of sweet potato to your evening meal or using quinoa as a base for a lunch salad.

Foods to limit for better vaginal health

While certain foods can help maintain a healthy vaginal microbiome, others may have the opposite effect. These foods don’t necessarily need to be eliminated entirely but being mindful of their intake and focusing on a balanced, nutrient-rich diet can support both vaginal and overall health.

High intake of animal protein

One study in pregnant women found that those who ate more animal protein before pregnancy especially from red and processed meats tended to have fewer Lactobacillus and a greater mix of other bacteria in the vagina, a pattern often linked with bacterial vaginosis10.

This doesn’t mean you need to cut out animal protein completely, but it may be beneficial to limit processed and high-fat meats and include more plant-based proteins like beans, lentils, tofu, and nuts for balance.

Tip: Try swapping one or two meat-based meals each week for plant-based dishes like lentil curry or chickpea salad.

High-fat and high-GI diets

Some research suggests that eating a lot of total fat, especially saturated fat, and regularly choosing high glycaemic index (GI) foods may have a negative effect on the gut microbiome, encouraging more pro-inflammatory bacteria.

In terms of vaginal health, one study in women of reproductive age found that diets higher in total fat and high-GI foods were linked to a more unstable vaginal microbiota. This type of imbalance may reduce the presence of protective Lactobacillus species and increase the risk of bacterial vaginosis. However, more high-quality studies are needed to confirm these links and understand exactly how diet may play a role11,12.

Tip: Swap refined carbohydrates for whole grains and choose healthy fats from sources like olive oil, nuts, seeds, and oily fish.

Alcohol

Studies have linked higher alcohol intake with an increased risk of bacterial vaginosis (BV) and a shift away from a Lactobacillus-dominant vaginal microbiota. This may be due to alcohol’s effects on the immune system, hormone metabolism, and the gut microbiome which could, in turn, influence vaginal health through the gut–vagina connection.

While the occasional drink is unlikely to have a big impact for most healthy women, frequent or heavy drinking may contribute to imbalances over time.

Tip: If you drink, try to keep within recommended limits of no more than 14 units per week, spread across several days.

Smart dietary swaps

Certain dietary choices may help support a healthy vaginal microbiome and overall wellbeing and a good place to start with some simple swaps and making these choices part of everyday life.

White bread, pasta, or rice → wholegrain versions to increase fibre intake and feed beneficial gut bacteria.

High-sugar yoghurts or dairy desserts → plain live yoghurt or kefir topped with fruit and seeds for added nutrients.

Processed meats (sausages, bacon) → lean poultry, oily fish, or plant proteins like lentils and chickpeas.

Fried foods cooked in saturated fats → meals cooked with extra virgin olive oil, rich in monounsaturated fats.

Sweetened soft drinks → water, sparkling water with citrus, or unsweetened herbal teas.

Ultra processed snack foods like crisps and pastries → nuts, seeds, or fresh fruit for a nutrient-dense alternative such as hummus with sliced vegetables.

Supporting vaginal health through diet isn’t about perfection or restriction, it’s about making everyday choices that nourish your body from the inside out. By focusing on fibre-rich plants, micronutrient-packed fruits and vegetables, quality protein, and beneficial fermented foods, you can help maintain a healthy vaginal microbiome while also supporting your overall wellbeing.

Miller, C., Morikawa, K., Benny, P., Riel, J., Fialkowski, M. K., Qin, Y., Khadka, V., & Lee, M. J. (2024). Effects of Dietary Quality on Vaginal Microbiome Composition Throughout Pregnancy in a Multi-Ethnic Cohort. Nutrients, 16(19), 3405. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16193405.

Lebeer, S., Ahannach, S., Gehrmann, T., Wittouck, S., Eilers, T., Oerlemans, E., Condori, S., Dillen, J., Spacova, I., Donck, L., Masquillier, C., Allonsius, C., Bron, P., Van Beeck, W., De Backer, C., Donders, G., & Verhoeven, V. (2023). A citizen-science-enabled catalogue of the vaginal microbiome and associated factors. Nature Microbiology, 8, 2183 – 2195. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-023-01500-0.

Amabebe, E., & Anumba, D. (2020). Female Gut and Genital Tract Microbiota-Induced Crosstalk and Differential Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids on Immune Sequelae. Frontiers in Immunology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.02184.

Shivakoti, R., Tuddenham, S., Caulfield, L., Murphy, C., Robinson, C., Ravel, J., Ghanem, K., & Brotman, R. (2020). Dietary macronutrient intake and molecular-bacterial vaginosis: Role of fiber.. Clinical nutrition. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2020.01.011.

Martinez, R., Franceschini, S., Patta, M., Quintana, S., Gomes, B., De Martinis, E., & Reid, G. (2009). Improved cure of bacterial vaginosis with single dose of tinidazole (2 g), Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1, and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.. Canadian journal of microbiology, 55 2, 133-8 . https://doi.org/10.1139/w08-102.

Leeuwendaal, N. K., Stanton, C., O’Toole, P. W., & Beresford, T. P. (2022). Fermented Foods, Health and the Gut Microbiome. Nutrients, 14(7), 1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14071527.

Corbett, G., Moore, R., Feehily, C., Killeen, S., O’Brien, E., Van Sinderen, D., Matthews, E., O’Flaherty, R., Rudd, P., Saldova, R., Walsh, C., Lawton, E., MacIntyre, D., Corcoran, S., Cotter, P., & McAuliffe, F. (2024). Dietary amino acids, macronutrients, vaginal birth, and breastfeeding are associated with the vaginal microbiome in early pregnancy. Microbiology Spectrum, 12. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.01130-24.

Rosen, E., Martin, C., Siega-Riz, A., Dole, N., Basta, P., Serrano, M., Fettweis, J., Wu, M., Sun, S., Thorp, J., Buck, G., Fodor, A., & Engel, S. (2021). Is prenatal diet associated with the composition of the vaginal microbiome?. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12830.

Miller, E., Beasley, D., Dunn, R., & Archie, E. (2016). Lactobacilli Dominance and Vaginal pH: Why Is the Human Vaginal Microbiome Unique?. Frontiers in Microbiology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01936.

Dall’Asta, M., Laghi, L., Morselli, S., Re, M., Zagonari, S., Patuelli, G., Foschi, C., Pedna, M., Sambri, V., Marangoni, A., & Danesi, F. (2021). Pre-Pregnancy Diet and Vaginal Environment in Caucasian Pregnant Women: An Exploratory Study. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2021.702370.

Song, S., Acharya, K., Zhu, J., Deveney, C., Walther-Antonio, M., Tetel, M., & Chia, N. (2020). Daily Vaginal Microbiota Fluctuations Associated with Natural Hormonal Cycle, Contraceptives, Diet, and Exercise. mSphere, 5. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSphere.00593-20.

Lehtoranta, L., Ala-Jaakkola, R., Laitila, A., & Maukonen, J. (2022). Healthy Vaginal Microbiota and Influence of Probiotics Across the Female Life Span. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.819958.